UBCO Engineering Professor Solomon Tesfamariam (centre) examines wood used in mass-timber buildings.

UBCO Engineering Professor Solomon Tesfamariam (centre) examines wood used in mass-timber buildings.

Posted in Business, Media Releases

Shahria Alam, co-director of UBC’s Green Construction Research and Training Centre and the lead investigator of the study.

Posted in Business, Media Releases

Posted in Media Advisory

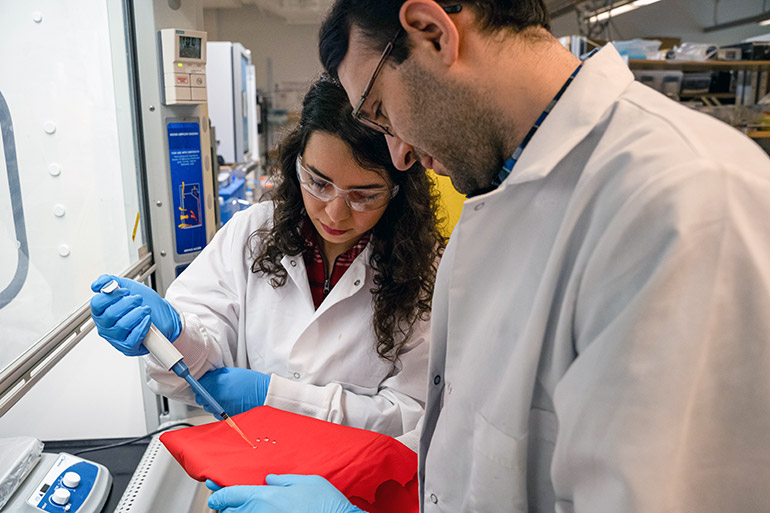

UBC Okanagan researchers Sadaf Shabanian (left) and Kevin Golovin (right) test water-repellent fabric treatment.

Posted in Media Releases, Research

UBCO associate professor Nelly Oelke is one of the researchers receiving funding from the interior university research coalition for her work in mental health resilience in rural communities

Posted in Media Releases

UBCO’s Cortnee Chulo wears a prototype 3D-printed face shield.

Posted in Media Releases

Posted in College of Graduate Studies, Spotlight

UBC Okanagan Engineering Professor Cigdem Eskicioglu has been named the Senior Industrial Research Chair (IRC) in advanced resource recovery from wastewater.

Posted in Business, Media Releases, Spotlight

Posted in Media Advisory

UBC Okanagan student Hafsah Khan is immersed in an operating room at the Hospital for Special Surgery at Weill Cornell Medical College in New York where a spine surgery is currently underway; although she is not physically there. The fourth-year mechanical engineering student is wearing a virtual reality headset to observe the surgery as part of an innovative new clinical engineering course being offered by UBCO.

“Clinical engineering is a field few people have heard of but it’s one that is likely to impact them directly if ever they find themselves in an operating room,” explains Sabine Weyand, an instructor at UBC Okanagan’s School of Engineering. “Our goal as clinical engineers is to make an operation as safe and efficient as possible.”

Weyand compares a surgery to a complex and well-choreographed dance with everything in its place and everyone with a role to play.

“Our job is to analyze every step of that dance, from the tools surgeons use to the lighting design to where people stand and how they interact,” she says. “It’s all dissected and analyzed to improve the mechanics of the procedure and, above all, patient care.”

UBC Okanagan student Hafsah Khan is immersed in an operating room at the Hospital for Special Surgery at Weill Cornell Medical College in New York where a spine surgery is currently underway; although she is not physically there. The fourth-year mechanical engineering student is wearing a virtual reality headset to observe the surgery as part of an innovative new clinical engineering course being offered by UBCO.

“Clinical engineering is a field few people have heard of but it’s one that is likely to impact them directly if ever they find themselves in an operating room,” explains Sabine Weyand, an instructor at UBC Okanagan’s School of Engineering. “Our goal as clinical engineers is to make an operation as safe and efficient as possible.”

Weyand compares a surgery to a complex and well-choreographed dance with everything in its place and everyone with a role to play.

“Our job is to analyze every step of that dance, from the tools surgeons use to the lighting design to where people stand and how they interact,” she says. “It’s all dissected and analyzed to improve the mechanics of the procedure and, above all, patient care.”

During the course, three types of surgeries are viewed including a hip replacement, a robotically-assisted knee replacement and a transforaminal lumbar inter-body fusion back surgery.

Weyand says local experts at the Interior Health Authority were key developing the course content and shaping the virtual reality labs.

“I wanted the experience to be as realistic as possible and to help students understand the real-world design challenges that they might encounter right here in the Okanagan,” she adds. “The clinical engineering course exposes students to clinical environments, a variety of diagnostic and treatment tools, as well as the complex human factors and regulatory requirements that accompany any surgical intervention.”

According to Khan, the reports are challenging because they require students to incorporate medical and anatomical vocabulary while understanding the procedure itself.

“It is definitely a big challenge, but fun to step outside of the traditional engineering lab environment and find ways to improve how these medical procedures are done.”

Interior Health also sees the value in providing UBC Okanagan engineering students with virtual reality experiences.

“These students, as future clinical engineers, need to have the latest information and technology at their fingertips,” says Aaron Miller, Director of Strategic Initiatives at Interior Health. “Virtual reality operating room observations are providing hands on experiences to see how the different healthcare providers work and provide direct patient care.”

He says that students that understand the needs of healthcare providers, are better able to support healthcare teams and improve patient outcomes.

Meanwhile back in the lab, Khan adjusts her eyes after removing her virtual reality headset. She says the course has already made a lasting impression.

“After this course, I am way more interested in pursuing a career in biomedical engineering.”

During the course, three types of surgeries are viewed including a hip replacement, a robotically-assisted knee replacement and a transforaminal lumbar inter-body fusion back surgery.

Weyand says local experts at the Interior Health Authority were key developing the course content and shaping the virtual reality labs.

“I wanted the experience to be as realistic as possible and to help students understand the real-world design challenges that they might encounter right here in the Okanagan,” she adds. “The clinical engineering course exposes students to clinical environments, a variety of diagnostic and treatment tools, as well as the complex human factors and regulatory requirements that accompany any surgical intervention.”

According to Khan, the reports are challenging because they require students to incorporate medical and anatomical vocabulary while understanding the procedure itself.

“It is definitely a big challenge, but fun to step outside of the traditional engineering lab environment and find ways to improve how these medical procedures are done.”

Interior Health also sees the value in providing UBC Okanagan engineering students with virtual reality experiences.

“These students, as future clinical engineers, need to have the latest information and technology at their fingertips,” says Aaron Miller, Director of Strategic Initiatives at Interior Health. “Virtual reality operating room observations are providing hands on experiences to see how the different healthcare providers work and provide direct patient care.”

He says that students that understand the needs of healthcare providers, are better able to support healthcare teams and improve patient outcomes.

Meanwhile back in the lab, Khan adjusts her eyes after removing her virtual reality headset. She says the course has already made a lasting impression.

“After this course, I am way more interested in pursuing a career in biomedical engineering.” Posted in Media Releases | Tagged Biomedical, Clinical, engineering, ENGR 450, Medical, school of engineering, Virtual, Weyand