Haile Woldesellasse in his home country of Eritrea.

Haile Woldesellasse in his home country of Eritrea.

Posted in College of Graduate Studies

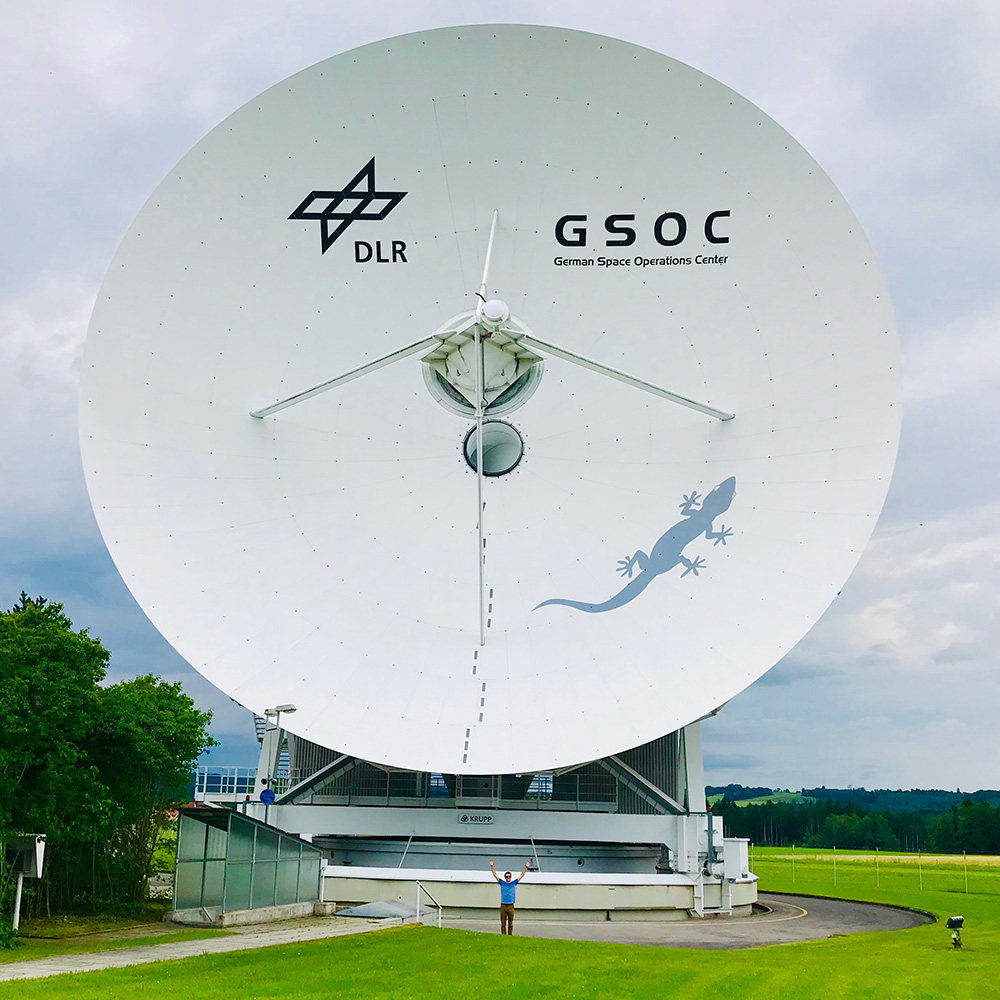

Ilija Hristovski stands at the base of a communications dish at the German Aerospace Centre, illustrating the dish’s impressive size. This particular dish is used for deep space communication.

Ilija Hristovski and former Canadian astronaut Dr. Robert Thirsk.

Posted in Uncategorized

Posted in Uncategorized

“I made my decision after my first meeting with her,” Uwamahoro says. “She’s very eager to learn and is interested in new things, new aspects. She tells you to question everything. I think those are the proper methods for a doctoral student.” Dr. Tobber was struck by Uwamahoro’s ambition and focus. She came to UBCO so she could one day return home and improve Rwanda. “I gravitate toward people who show leadership and perseverance,” Dr. Tobber says. “I like people who see the world differently. All of those things really resonated when I met Chadia.” Uwamahoro’s specific research is around precast concrete buildings and systems, with emphasis on the connections being used with precast concrete shear walls. A precast system is constructed in a plant and transported to the building site, while traditional systems are poured on location. “Precast is already being used in Canada, especially Ontario,” Uwamahoro says. “It involves multiple different units that need to be connected to act as one building. We’re looking at those connections and how they behave.” Precast concrete is seen as vital to reducing greenhouse gas emissions and making construction more environmentally friendly. It can be more affordable than traditional concrete buildings, making precast an economical option when addressing the housing crunch. “There isn’t enough of this type of research happening in the world,” Dr. Tobber says. “It’s vital we adopt new technologies and new materials to help address climate change, housing insecurity and even natural disaster.” Uwamahoro doesn’t intend to stop at concrete. Her future work, she says, will remain on the pursuit of a Rwandan building code and her consulting company. She wants to continue helping disadvantaged communities with initiatives and programs that help build houses for refugees. “The Rwandan building code being used right now was taken from the United Kingdom,” she says. “We don’t have one based on current data in Rwanda. I want to be able to create a building code for Rwanda and Dr. Tobber understood that. She was willing to give me the space, and that’s incredible.” She says that bringing her two worlds together—taking what she learned at UBCO with her home to Africa—is proof everyday Rwandans are invested in their future. “Rwanda has reconciled,” she says. “The government is consulting people, teaching children what happened and what hatred can do to people. As a country, we don’t want what happened to repeat. “To quote our president, Paul Kagame, ‘We cannot turn the clock back nor can we undo the harm caused, but we have the power to determine the future and to ensure that what happened never happens again.’” The post Chadia Uwamahoro is helping Rwanda rebuild appeared first on UBC Okanagan News.“I gravitate toward people who show leadership and perseverance. I like people who see the world differently. All of those things really resonated when I met Chadia.” – Dr. Lisa Tobber

Posted in Uncategorized

These tellurium-boosted lithium-sulfur batteries are being tested for their lithium-ion storage and cycling stability, as well as their internal reaction mechanism. Researchers discovered that the new battery technology contributes to more power, meaning extended mileage for electric vehicles.

Posted in Uncategorized

Posted in Uncategorized

Dr. Cherian with Dr. Sumi Siddiqua of UBCO’s School of Engineering.

After completing her Mitacs fellowship, Dr. Cherian immersed herself in teaching opportunities in the School of Engineering. “I tell my friends that when you’re a teacher, you don’t age, you always feel like a student yourself.” She has formed strong relationships with her diverse group of students and credits being a mother as having informed her teaching style. “Through my son and daughter, I’ve learned to appreciate that different people have different perspectives and needs that must be met.”

This appreciation was the catalyst for Dr. Cherian’s esteem for the Disability Resource Centre and the Equity and Inclusion Office. “We see such positive outcomes with the implementation of these services at UBCO,” she says. “It’s my goal to advocate for the support of students from a variety of facets including mental health and the removal of barriers to education, especially in places where these pillars don’t exist.”

Dr. Cherian is thrilled to be extending her work with Dr. Siddiqua as a Research Engineer in the School of Engineering and hopes to continue sharing her passions for civil engineering, diversity and sustainability with students as a Sessional Instructor this fall.

The post Dr. Chinchu Cherian successfully balances motherhood, research and teaching appeared first on UBC Okanagan News.

After completing her Mitacs fellowship, Dr. Cherian immersed herself in teaching opportunities in the School of Engineering. “I tell my friends that when you’re a teacher, you don’t age, you always feel like a student yourself.” She has formed strong relationships with her diverse group of students and credits being a mother as having informed her teaching style. “Through my son and daughter, I’ve learned to appreciate that different people have different perspectives and needs that must be met.”

This appreciation was the catalyst for Dr. Cherian’s esteem for the Disability Resource Centre and the Equity and Inclusion Office. “We see such positive outcomes with the implementation of these services at UBCO,” she says. “It’s my goal to advocate for the support of students from a variety of facets including mental health and the removal of barriers to education, especially in places where these pillars don’t exist.”

Dr. Cherian is thrilled to be extending her work with Dr. Siddiqua as a Research Engineer in the School of Engineering and hopes to continue sharing her passions for civil engineering, diversity and sustainability with students as a Sessional Instructor this fall.

The post Dr. Chinchu Cherian successfully balances motherhood, research and teaching appeared first on UBC Okanagan News. Posted in College of Graduate Studies

“More perspectives and lived experiences are needed to responsibly address yesterday’s faults, today’s challenges and tomorrow’s opportunities. Only then can the natural creativity and full capacity of engineering become a reality.”His current research involves developing technologies made from DNA, using the structural integrity, information density and programmability of life’s most basic material. Such technologies range from engineering low-cost liquid computers that perform early stage diagnostics of hard-to-detect diseases, to storing extremely dense and stable information for archival applications. Using the triple-bottom-line as a guide, Dr. Hughes and his multidisciplinary team have always been committed to the social, environmental and financial impacts of their work. In collaboration with the Micron School of Materials Science & Engineering at Boise State, Harvard University, and the Semiconductor Research Corporation, Dr. Hughes coined the field Nucleic Acid Memory. He then envisioned and contributed to the semiconductor synthetic biology roadmap to steer semiconductor investments in a post Moore’s Law world. “Moore’s Law suggests that the power of computers and electronics doubles every two years,” explains Dr. Hughes. He sees a similar growth in the power of inclusion, community and engineering. He envisions the School of Engineering as both a welcoming place and creative space where engineering is a verb, not a noun. “I see in the people around me what a few people saw in me—potential energy. The potential to serve our community one person, one idea and one expression at a time by helping create the conditions for responsible growth and innovation to happen at scale.” The post Deliberate with actions and ambitious with dreams appeared first on UBC Okanagan News.

Posted in Uncategorized

Posted in Uncategorized

“In 10 years, I know I’ll definitely still be teaching. Ask me again in 20 years, and I‘ll still say teaching. That’s what I want to do for the rest of my life.”As a researcher of control systems and autonomous vehicles, Dr. Shirazi’s work often looks to the future. As both an educator and an engineer, he looks for opportunities to innovate his practices while being mindful of the impacts on his students and the world. But he also wants to help his students succeed in more than just academics, ultimately forming the skills they need to be great engineers as well as family members, friends and citizens. “I want to give them confidence so they know they can be successful. I tell my students they’re not here for grades; they’re here to learn.” He adds: “My work is to support my students’ learning while maintaining their mental health and wellbeing. That’s the ultimate goal.” Dr. Shirazi still keeps in touch with many of his earliest students—the classmates he tutored in Iran who inspired him in his teaching journey. “Many of my old students have become very successful, working and studying in places all around the world. When I hear the effect I’ve had in their lives, both during the semester and after they graduated, that makes me so happy.” As for his own future, Dr. Shirazi is certain what it will hold. “In 10 years, I know I’ll definitely still be teaching. Ask me again in 20 years, and I‘ll still say teaching,” he laughs. “That’s what I want to do for the rest of my life.” The post Dr. Mehran Shirazi is a lifelong teacher appeared first on UBC Okanagan News.

Posted in Uncategorized