Dr. Shahria Alam conducts research in the seismic analysis and rehabilitation of steel, concrete and masonry. His latest research examines variations in the strength and mechanical properties of rebar to determine if the product meets Canadian safety standards.

A truck, along with hundreds of other vehicles filled with drivers and passengers, rumbles over the Alex Fraser Bridge.

The drivers probably never give a second thought to what is holding up that bridge—what makes it safe. Below, and embedded into the bridge deck and piers, are tens of thousands of pounds of steel rebar. The rebar, a skeleton integrated within the concrete, provides strength to the structure and reinforces the bridge’s seismic integrity.

But how do engineers know how much rebar to use? Should it be thicker? Stronger? Is the bridge protected in case of an earthquake?

“During a seismic event, the rebar serves two purposes,” says Dr. Shahria Alam, Civil Engineering Professor at UBC Okanagan’s School of Engineering. “It helps keep pieces intact during small earthquakes and it ensures safety while sustaining damage during major earthquakes.”

Rebar comes in a variety of configurations based on strength, ductility, length and diameter, he explains. The challenge engineers face is the uncertainties associated with the materials used to make structural designs safe, efficient and predictable.

Concrete, reinforced with rebar, plays a vital role in providing resistance, but variations in the rebar’s mechanical properties can increase uncertainty in the assessment of existing structures and the design of new structures. The production of steel rebar involves several steps, including purifying, alloying, rolling and temperature treatment, which could have an impact on its mechanical properties.

Factors that can affect rebar’s strength include the microalloying stage—when elements such as carbon and manganese are added to the steel to make it stronger—as well as the source of the mill.

“The mechanical properties of steel rebar are reliant on the manufacturing processes within any given mill,” says Dr. Alam. “In this scenario, it’s not only the size but also the tensile strength and the material’s ability to withstand repeated stress and deformation that matters.”

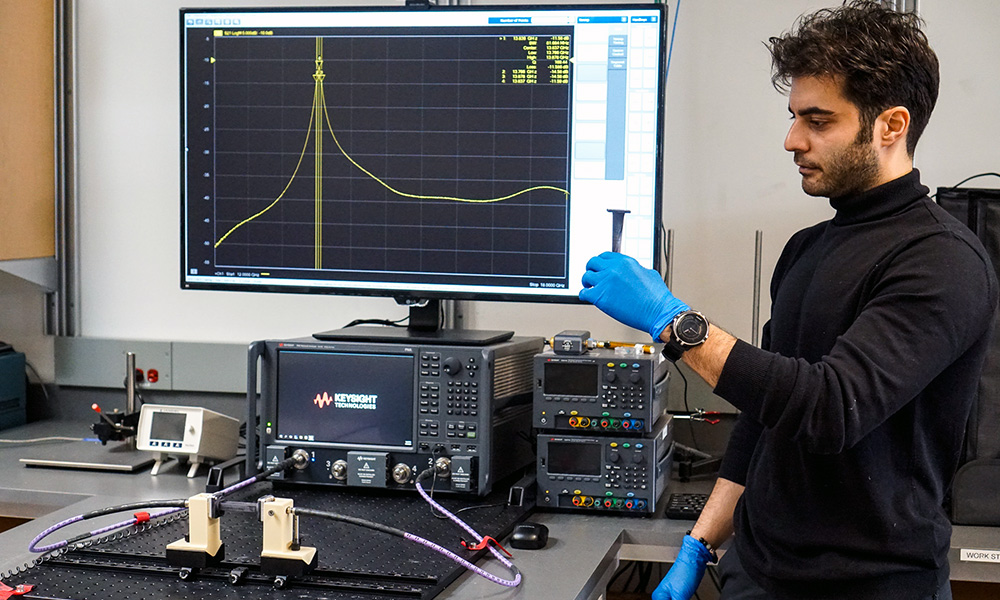

Dr. Alam explains that the Canadian Standards Association sets out requirements in the bridge design code to ensure that all rebar performs predictably. His team of researchers at UBCO’s Applied Lab for Advanced Materials & Structures recently completed a study examining different types of rebar to see if it was indeed meeting North American design standards.

The researchers examined tensile test data, provided by the Concrete Reinforcing Steel Institute to investigate the variability of mechanical properties across a few parameters including mill source, bar size and weight per metre.

The data was also compared to the minimum requirements of the American Society for Testing and Materials (ASTM)

“Our most recent research sought to investigate the recent variability of mechanical properties, specifically the yield and ultimate tensile strength of steel rebars in North America.”

Their study showed that only a fraction (0.12%) of the strength test results didn’t meet the basic safety standards. This means that if buildings are designed according to the official codes and with extra safety margins built in, the structures will be sufficiently safe.

The research is supported by the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada, the British Columbia Ministry of Transportation and Infrastructure and the engineering consulting firm WSP Canada through an Alliance grant. It was published in the latest edition of the journal Engineering Structures.

The post When it comes to rebar, stronger doesn’t mean better appeared first on UBC Okanagan News.